pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Rogue Shark! The Jersey Shore Attacks of 1916 Part One: Killer on the Loose July 1, 1916, was a fine day at the New Jersey resort town of Beach Haven. The surf rolled in and broke against the warm sands. The beach was filled with people who had taken the train down from Philadelphia to beat the city heat. One young man named Charles Vansant, 25, son of a doctor from Philadelphia, was staying with his family at the posh Engleside Hotel that overlooked the beach. He decided to take a quick swim before dinner and plunged into the surf followed by his dog. Vansant was a good swimmer. He swam straight out into the ocean, showing those on the beach he was not afraid of the deep water. The dog followed him obediently. Then the animal suddenly turned around and swam back to the beach. Charles tried to encourage it to return to the water, but it wouldn't. Ready for dinner, Charles started swimming back himself. Then someone on the beach noticed a fin emerging out of the deep blue water behind him. It moved swiftly closing the distance with the young man. Cries of "Watch Out!" filled the beach, but Charles never heard them over the pounding surf. He was in only three and a half feet of water when it finally happened. Spectators on the beach saw a huge triangular head rise out of the water. Jaws filled with sharp teeth opened and clamped down on Vansant's left leg just below the knee. The young man screamed as his blood turned the surrounding water red. Men rushed into the water to help the swimmer. Alexander Ott reached him first and grabbed Vansant under the arms. When he tried to tow Vansant out of the water, however, he found he was in a tug-of-war with a ten-foot-long, black, torpedo-shaped animal under the surface. As more men joined the struggle they began to win, pulling Vansant and his attacker onto the beach. As the animal's body finally scraped bottom, however, it let go and swam for deep water. Vansant was carried to the hotel, bleeding from a torn femoral artery with much of his left leg missing. Despite the efforts of his father, a doctor, he died within the hour. His wounds were so severe that even with the modern medical techniques and fast emergency transport available today, nearly a century later, it is unlikely he would have survived. He was the first victim of the Jersey Shore man-eater of 1916. Shark, Mackerel or Giant Sea Turtle? The next day the headline in the New York Times read, "Dies After Attack by Fish." Definitely Vansant was killed by a sea creature, but what kind? Today, most people's first reaction was that it must have been a shark. That wasn't a fact that was obvious to most people in 1916, including many prominent scientists. There had never been a documented case of a shark attack on American shores before. Shark attacks seemed the thing of old sea tales. Many people were just as willing to believe the attacker was a giant mackerel or a huge sea turtle rather than a shark. On July 6th, forty-five miles north of Beach Haven at Spring Lake, New Jersey, most people were unconcerned about the reports of the attack a few days before. The local paper, The Asbury Park Press, seemed skeptical that an attack had even taken place. Perhaps Vansant had simply drowned and the part about the shark had been fabricated, it suggested.

In any case, 19 year-old Robert Dowling and Leonard Hill, a druggist from New York City, separately planned long swims along the coast that day. Both were not worried about the reports from Beach Haven. Both were also unaware, until later, they would be swimming with a man-eating sea monster nearby in the water. Despite this they took their swims and returned alive. Just a few minutes later a man by the name of Charles Bruder entered the water for his swim. The Spring Lake Attack Bruder was a twenty-five year old Swiss bellhop at the swanky Essex and Sussex hotel. He was a well-known figure in Spring Lake and his form could be seen swimming in the ocean every summer day during his late afternoon break. He often boasted that while living in California he had swum many times with large sharks and was unafraid of them. That day he swam straight out into the sea for over a thousand feet. Then suddenly something came up behind him. Bruder never saw the monster until it struck. "He was a big gray fellow, and as rough as sandpaper," said the bellhop as he lay dying. "He cut me here in the side, and his belly was so rough it bruised my face and arms. That was when I yelled the first time. I thought he had gone on, but he only turned and shot back at me and snipped my left leg off." From the beach people had seen a huge spray of water erupt from the surface of the sea. One woman called, "The man in the red canoe is upset!" There was no canoe. The red was Bruder's blood spreading out across the water. Lifeguards raced out to him in their small rescue rowboat and saw a black shape under the water striking at the man over and over again. When they finally were able to pull him into the boat they were surprised at how amazingly light he was - until they saw that both his legs had been bitten off. Bruder lay in the bottom of the boat, bleeding, while the lifeguards rowed for shore. He briefly described his ordeal to them then lost consciousness, never to awake again. That day Dowling and Hill both vowed to give up long-distance, ocean swimming. Dr. William G. Schauffler, the governor's staff physician and a surgeon in the National Guard, examined Bruder's body on the beach.. Schauffler was a fisherman himself and sure as to the cause of the bellhop's death: "There is not the slightest doubt that a man-eating shark inflicted the injuries," he reported. Schauffler was convinced the creature, a confirmed man-eater, would not stop at one victim. As soon as he was done with examining the body he was planning to organize a patrol of armed men and a fleet of boats to put an end to the killer shark.

If Schauffler had no doubt about the identity of the animal, Dr. John T. Nichols, an ichthyologist (a fish expert) from the American Museum of Natural History, was more uncertain. He had come down from New York, examined Bruder's remains and come to a different conclusion. Nichols told reporters at Spring Lake that he believed the culprit was an Orcinus orca, otherwise known as a "Killer Whale." As the New York Times put it, "Mr. Nichols thought there was as much reason to suppose it was a killer whale as to suppose it was a shark." His conclusion was reasonable given what was known about the orcas in 1915. From the earliest times this animal was thought by sailors to be a man-killer. It wasn't until the 1960's and 70's that scientists realized that the orca was the smartest member of the dolphin family and there were really no documented cases of the creature ever killing a man. Patrol boats were put into the water, but the next deadly incident during that hot summer of 1916 did not occur at Spring Lake. Nor did it occur anywhere along the Atlantic beaches of New Jersey. Indeed, it occurred at about the most unlikely place that anyone might think of. The Monster of Matawan Creek The small town of Matawan was fifteen miles from the Jersey shore connected to the ocean by the Matawan Creek. The creek was tidal and filled with brackish water - the result of the salty sea mixing with the fresh water stream. In the summer of 1916 teenage boys would meet to swim down at the old lime works factory where the creek widened to 30 feet as it made a turn. On the afternoon of July 11th, 14-year-old Rensselaer Cartan was splashing in the creek with his friends when something big with skin as rough as sandpaper brushed by him. He screamed and scrambled out of the water onto the dock. His chest was scratched and bloodied. None of the other boys with him saw anything and many went back into the creek after Cartan left to get his wounds bandaged.

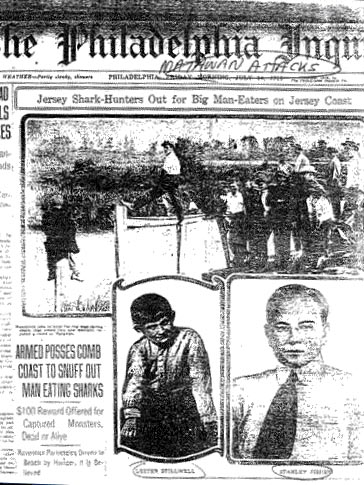

The next day 59-year-old Thomas Cottrell, a retired sea captain, was taking his morning walk along the creek when he saw something very unusual: as he crossed the trolley bridge the Captain looked down into the water and spotted a dark-gray shape moving up the creek. He estimated the fish was nine or ten feet long with a tall dorsal fin cutting through the water. Cottrell immediately knew what it was: a shark. He'd seen plenty of them at sea and knew what they could do to living prey. He was shocked to find one in the creek and immediately connected it to the story he heard about Rensselaer Cartan. The captain raced into the town of Matawan to the shop of the barber, John Mulsoff, who was also the village's constable. The captain's story was met with disbelief and ridicule. How could a huge shark live in a creek that was only a foot deep at low tide? With no help to be found from the police, Cottrell decided to take it upon himself to warn the populace along the water way. He climbed into his small motorboat and headed up the creek, shouting to everyone he met a warning about the shark. The warning had either not reached 11-year-old Lester Stilwell or he had ignored it. He was playing with his friends in the creek near the Wyckoff dock at about 2:00 PM that day when he was attacked. The other boys around him saw "the biggest, blackest fish" they'd ever seen rise up out of the water and hit the boy. One witness said he saw, "Lester, being shaken, like a cat shakes a mouse…" The shark and the boy then disappeared into the muddy water. The boys, who had been skinny dipping, did not even bother to get dressed but ran into the middle of town naked screaming "Shark! A shark got Lester!" At this two of the town's best swimmers, Stanley Fisher and George Burlew, donned their swimming trunks and headed to the creek to search for the body. By the time they arrived at the location where the boy had disappeared there was a crowd of people along the bank. Fisher and Burlew strung chicken wire across a shallow section of the creek so the tide would not take the body out to sea, than began using a rowboat and long poles to search for Lester's body. After an hour of searching, however, and perhaps doubting there had been a shark attack at all, they decided to enter the water themselves to try and find the remains of the boy. They swam and dove in the area for a half hour without success. Finally Burlew started swimming back to the dock, but Fisher decided to make one more try. He came up shouting, "I've got it!" Two men took a rowboat out to help him with Lester's body when suddenly Fisher shouted, "He's got me!" The shark had attacked Fisher. He struggled with the creature and it struck at him multiple times pulling him under the water. Finally Fisher managed to make it to shore. When he was pulled from the water half the flesh on his right thigh had been taken off by the shark's powerful jaws. Eight o'clock that evening Fisher died on the operating table at Monmouth Memorial Hospital of massive blood loss and shock.

Three-quarters of a mile further down the creek and thirty minutes later near a local brickyard, Jerry Hourihan and brothers Joseph and Michael Dunn were cooling off in the water. None of them were aware of the attacks earlier in the day. As they were swimming, though, a voice warned them about the shark in the water and they began swimming towards the dock. Twelve-year-old Joseph was still ten feet from safety when something fast and large brushed by him scratching his skin. Turning back the shark clamped down on his leg. The monster tried to pull the boy into deeper water, but Jacob Lefferts (who had been out giving shark warnings) and Michael Dunn leapt into the water to assist Joseph. When they finally got him out of the water onto the brickyard's pier, much of the flesh on his left leg was stripped away. Fortunately for Joseph Dunn, the shark's jaws had neither crushed his bones nor torn an artery and he survived the attack. All over town now the word had spread that one or more man-eating sharks were in the creek's waters. Men in boats armed with guns patrolled the surface looking for signs of the monster. Sticks of dynamite were thrown into the water at the sign of any suspicious ripple along the surface. A steel mesh net was dropped at the mouth of the creek so the murderous creature could not escape. By the next afternoon, however, when the nets were examined, it was clear that the man-eater had gotten away. Something big had chewed its way through the steel cables and headed back out into the bay. Part Two: With four dead and one gravely injured, the public panics and the hunt for the killer shark begins. Copyright Lee Krystek 2009. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|