|

Stonehenge:

Mystery on the Salisbury Plain

|

Stonehenge, in many peoples' minds, is the most

mysterious place in the world. This set of stones laid out in

concentric rings and horseshoe shapes on the empty Salisbury

Plain, is, at the age of 4,000 years, one of the oldest, and

certainly best preserved, megalithic (ancient stone) structures

on Earth. It is a fantastic creation with the larger 25-ton

Sarsen (a hard type of sandstone) stones transported from a

quarry 18 miles away. Some of these boulders also carry massive

lintels connecting them. In ancient times, when all the stones

were standing, there was a ring of rock in the sky as well as

on the ground.

Who Built It?

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| When

Built: Earthworks and timber about 3100 B.C., first

stones 2600 B.C. |

| Heaviest

Stones: 50 tons |

| Made

of: Sarsen sandstone and Bluestone rock. |

| Design:

Upright stones and earthworks in a series of concentric

circles and horseshoe shapes. |

| Function:

Unknown, but researchers suspect it was used for ceremonial

and religious purposes. |

| Built

by: An unknown people without a written language. |

| Other:

Designed to be used for astronomical observations including

summer solstice. |

We know almost nothing about who built Stonehenge

and why. A popular theory advanced in the 19th century was that

the Druids, a people that existed in Britain before the Roman

conquest, had built it as a temple. Modern archaeological techniqueshave

dated Stonehenge and we now know that it was completed at least

1,000 years before the Druids came to power. If Druids used

Stonehenge for their ceremonies, they got the site secondhand.

Despite this, modern Druids have laid claim to Stonehenge. An

annual ceremony takes place at the ring of rocks during summer

solstice, one of the henge's astronomical alignments.

There is evidence that activity on the Stonehenge

site goes as far back as 11,000 years ago. It wasn't until about

3100 BC, though, that a circular bank following the current

Stonehenge layout appeared. At the same time pine posts were

put into place. Around 2100 BC stones started being erected,

at first the smaller bluestones, then the larger sarsens stones.

During this period some stones were erected, then later dismantled.

Why did the builders create, dismantle and rebuild

this isolated site? It's hard to say. They apparently didn't

have a written language and left no records. We can say one

thing about Stonehenge based on archaeological digs at the location.

There is almost no "trash." A number of pieces of flint, antler

picks or axes have been found, but very few items that one would

expect to see discarded at a human habitation This leads some

archaeologists to conclude that Stonehenge was "sacred ground,"

like a church. As one scientist put it Stonehenge was a "clearly

special place where you didn't drop litter."

|

Stonehenge

around 1500 BC. (Copyright Lee Krystek,

1997)

|

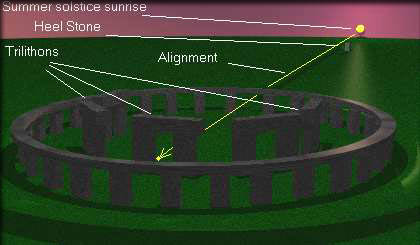

At about 1500 BC Stonehenge consisted of a circular

ditch with a raised bank on the inside. Within the bank was

a circle of 30 sarsen stones with lintels creating a raised

circle. Today only 17 of those stones still stand and few of

the lintels are still in position. Within the ring were five

"trilithons" (two massive upright stones supporting a lintel)

arranged in a horseshoe. On the open side of the horseshoe,

outside the ditch, was the heel stone, some 120 feet from the

ring. Once a year on summer solstice (the longest day of the

year), the sun will rise in alignment with the heel stone as

seen from the center of the ring.

In addition to the sarsen stones there was a less

elaborate set of blue stones that scientists believe were transported

to the site from Wales, 150 miles away. Some sit in a ring outside

the trilithons and the others in a horseshoe within the trilithon

horseshoe. There are also four "station stones" set in a rectangle

outside the ring. The station stones may have been used to predict

the movement of the moon.

Rings of Rock

Perhaps what is strangest about Stonehenge is

that it is far from being unique. Though Stonehenge is the most

intact and elaborate ring of stones, there are known to be over

a thousand remains of stone circles throughout the British Isles

and Northern France. Some of them were small, like Keel Cross

in County Cork which is just 9 feet in diameter. The largest,

Avebury covers over 28 acres and encircles what is now a whole

village. Some of the stones at Avebury weighed 60 tons.

|

A

modern summer soltice celebration at Stonehenge. (Photo

by Andrew Dunn licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share

Alike 2.0 Generic license.)

|

How did the makers move these massive rocks many

miles? In 1136 in his History of the Kings of Britain

Geoffrey of Mammoth suggested that the movement of these huge

stones was done through the magic of Merlin the wizard. More

likely, however, the builders moved them by dragging them on

wooden sledges. Before the first one could be moved a road had

to be cleared from what was then a thick forest. Not an easy

job in itself, especially for a people who probably spent most

of their time and energy just fighting for survival. The construction

of both Avebury and Stonehenge must have been the work of many

generations.

The Corral Theory

Just as fascinating as how the builders constructed

the site is the question of why they created it. Archaeologist

Clive Waddington has suggested that the earliest henges, simple

ditches with surrounding mounds, may have been stock enclosures

for cattle. Remains of fence and gates found at the Coupland

Henge, which is more than 800 years older than Stonehenge, supports

his idea. Waddington thinks that when cattle were moved into

the enclosure during certain seasons, rituals were performed.

As time went on the circles functional aspect faded away and

they became purely religious structures.

Most of the rings were smaller than Avebury and

simpler than Stonehenge. While some of them had astronomical

alignments built into their design, many did not. This suggests

that their use as observatories may have been a secondary function.

A "Place of Healing?"

|

Professor

Geoffrey Wainwright thinks that Stonehenge may have served

as a "place of healing." (Photo by Dorieo21

licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

license)

|

Another recent suggestion by Professor Tim Darvill

of Bournemouth University and Professor Geoffrey Wainwright

of the Society of Antiquaries of London is that Stonehenge may

have served as a "place of healing." Excavations of graves in

the area show that the remains of people buried there display

signs of serious disease or injury. Testing also indicates that

about half of those people were from outside the Stonehenge

area. "People were in a state of distress, if I can put it as

politely as that, when they came to the Stonehenge monument,"

said Darvill. Also puzzling is a large number of chips found

that were flaked off the bluestone of the monument. "It could

be that people were flaking off pieces of bluestone in order

to create little bits to take away… as lucky amulets," said

Professor Wainwright. The professors think that the place may

have been similar to Lourdes, the French shrine known for its

supposed ability to heal the sick. This evidence, however, does

not rule out other uses for Stonehenge. "It could have been

a temple, even as it was a healing center," Darvill said. "Just

as Lourdes, for example, is still a religious center."

Domain of the Dead or British Unification?

The area around Stonehenge has a large number

of burials and this has lead Professor Mike Parker Pearson of

Sheffield University to suggest that it is a domain of the dead,

while a Neolithic settlement nearby was the corresponding place

of the living. More recently, Professor Parker has championed

the idea that Stonehenge was built to unify the different peoples

of the British island. "There was a growing island-wide culture

-- the same styles of houses, pottery and other material forms

were used from Orkney to the south coast," says Pearson. "This

was very different to the regionalism of previous centuries."

Pearson also points out that a site as big as

Stonehenge would have required cooperation among many groups.

"Stonehenge itself was a massive undertaking, requiring the

labor of thousands to move stones from as far away as West Wales,

shaping them and erecting them. Just the work itself, requiring

everything literally to pull together, would have been an act

of unification," he explains.

So was Stonehenge a corral, a religious center,

a place of healing, or symbol of British unity? Or was it all

of the above? Scientists may never be able to say for sure.

As Professor Richard Atkinson of University College, Cardiff,

a researcher at Stonehenge, once said, "You have to settle for

the fact that there are large areas of the past we cannot find

out about..."

|

Stonehenge

at sunset. (Photo by Jeffrey Pfau licensed

under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

Unported license)

|

Copyright Lee Krystek

1997, 2012 . All Rights Reserved.