|

Building

the

Bell Rock Lighthouse

|

In December

of 1799, a terrible storm hit the northeast coast of England

and Scotland. Monstrous seas ripped ships from their moorings

and slammed them up against the coast. Out in the deep water,

ships still at sea were tossed and crushed by gigantic, violent

waves. By the time the storm let up after three days some 70

ships had been sunk and the lives of many seafaring men had

been lost.

In Scotland,

the Firth of Forth, the bay of Scotland's River Forth, would

have provided a haven for many ships in danger from that terrible

storm. However, none dared approach it because of a treacherous

quarter-mile-long reef there called the Bell Rock. Emerging

from the water for only short periods during the day, most of

the time Bell Rock lay invisible just below the waves, ready

to rip the bottom out of any ship that made for the safety of

the bay. The rock was considered so dangerous that many ships

chose to risk riding the storm out at sea rather than try to

make it past the reef to safety.

The

Abbot's Bell

Fear

of the reef (which was also known by the name of Inchcape Rocks)

was instilled in sailors long before the great storm of 1799.

According to some sources in the 14th century, the Abbot of

Aberbrothock, John Gedy, and some of his monks sailed out to

the rock with an enormous bell. They successfully attached it

to the reef so that the waves would make it ring continually,

giving ships an audible warning. The bell stayed on the rock

for only one year, however, before it was stolen by the Dutch

pirate "Ralph the Rover." Ironically, according to the story,

the pirate himself perished on the rock when his ship broke

upon it because he had taken the warning bell.

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| -Location:

On the Bell Rock reef 11 miles off the Northern Coast

of Scotland. |

| -Height:

From the foundation to top is 115 feet, 10 inches (35m). |

| -Made

of: Granite and Sandstone. |

| -Construction

Dates: August 1807 to February 1811. |

| -Construction

Crew: Approximately 110 men. |

| -Cost:

£61,331 |

| -Other:

Construction of the lighthouse claimed 5 lives.

|

The

bell had one lasting effect, however. It gave the dangerous

reef a name that would last through the centuries.

No further

attempts were made to place a warning device on the rock for

hundreds of years. In the late 18th century, however, the Northern

Lighthouse Board was established. By 1795 there were seven major

lighthouses along the coast of Scotland. However, the Bell Rock,

which was under sixteen feet of water at high tide, was still

considered by almost everyone too difficult a place upon which

to build a lighthouse.

Robert

Stephenson

However

a young engineer named Robert Stephenson felt differently. Stephenson

was employed by the Board to inspect and repair the existing

lighthouses and survey locations for new ones. He was intrigued

with the idea of placing a light on Bell Rock, but many members

of the board felt that it was simply impossible and would not

entertain his proposals. The disastrous storm of 1799, however,

showed that many ships and lives might be saved if only a warning

light could be built on the reef. In October of 1800, Stephenson

finally found a fisherman brave enough to take himself and architect

James Haldane the 11 miles out to the rock for a couple of hours

to take a closer look at it.

The

pair found that the part exposed at low tide was about 250 feet

long, 130 feet wide and composed of sandstone. Stephenson had

gone out to the rock expecting to build a structure over it

supported by pillars, but then determined after his examination

that these would never stand the pounding of the storm waves.

Instead, Stephenson decided to take a page from the book of

engineer John Smeaton who designed the Eddystone Lighthouse

near the port of Pymouth.

|

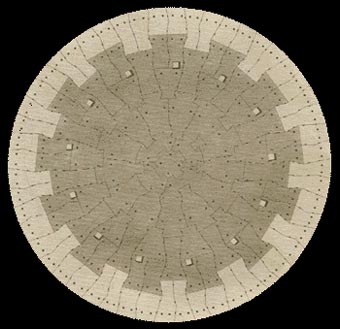

A

diagram showing the interlocking stones at the base of

the lighthouse.

|

The

Eddystone Lighthouse had been built in 1759 on an exposed rock

that was swept by the sea. Two earlier lighthouses on the same

location had tragically collapsed, but in his design Smeaton

had used a clever scheme of interlocking heavy granite blocks

with dovetail joints and marble dowels to ensure that the stones

could not be pulled apart even by the most powerful waves. He

also gave the lighthouse an inward, curved shape similar to

an oak tree trunk which he thought would resist the sea. His

structure was successful and inspired Stevenson to use a similar

design on Bell Rock.

However,

the Bell Rock construction would be considerably more difficult

than what had been done at Eddystone. The rock at Eddystone

was above sea level under normal conditions whereas Bell Rock

was covered by nearly 16 feet of water at high tide and was

only four feet above the waves at low tide. This meant that

the new lighthouse would need to be at least 20 feet higher

than Eddystone, with a correspondingly larger base. This 40

foot wide base meant that more than 2,500 tons of stone would

be needed to build the tower. Stephenson estimated that the

cost would be a staggering 42,000 British pounds.

Because

of the high cost, the lighthouse authority was reluctant to

pursue the project. Then, in 1804, the 64-gun man-of-war, HMS

York, went missing on a routine patrol in the North Sea. It

was later determined that the ship hit the rock and sank with

all 491 hands on board.

Appeal

to Rennie

Despite

this, resistance to Stephenson's plans continued as it was thought

that he was too young and untried to take on such a difficult

project. Stevenson finally wrote a letter about his plan to

John Rennie, one of the most well-known civil engineers in the

country. Rennie looked over Stephenson's materials and was impressed.

With Rennie involved, approval was finally forthcoming, with

Parliament passing legislation allowing the board to borrow

$25,000 pounds to cover the cost. Rennie was put in charge,

with Stephenson as his assistant.

|

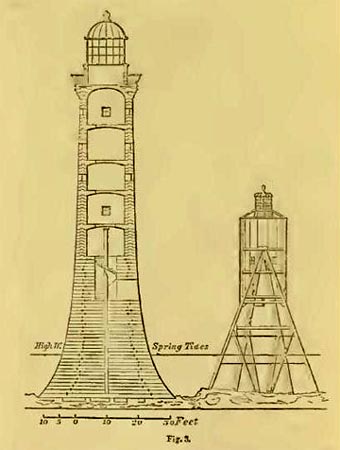

A

diagram showing a cross section of the lighthouse and

the associated beacon house.

|

Despite

Rennie and Stephenson agreeing that the design was workable,

there were a lot of unknowns about the project. Nobody had ever

attempted to build a lighthouse where the base was so far underwater

and the location was so distant from land. How would they house

the construction crew?

There

were three vessels that would be involved in the erection of

the lighthouse. The "Pharos" (named after the Pharos lighthouse

of ancient Alexandria) was 67 feet long and would be moored

about a mile and a half to the northwest of the site to act

as a temporary floating lighthouse during construction. The

"Smeaton" (55 feet long) was especially built for the project

and served as a tender for the floating light as well as a way

to transport the giant granite blocks out to the site from the

mainland where they were being cut and shaped. It was decided

that a third ship, the "Sir Joseph Banks", would be built to

house the construction crew. However, the "Joseph Banks" was

still under construction on the day the crew started out to

the site on August 17th, 1807.

Construction

The

crew was instead housed on the Smeaton and later the Pharos.

Only a few hours of work could be done twice a day a low tide

while the rock was exposed. The crews were expected to live

on the ships for a month at a time while construction was underway

and row out to the rock in small boats during the work periods.

A near disaster occurred early on when the Smeaton broke its

moorings and could not be brought back before the crew working

on the rock would have been drowned by the incoming tide. Fortunately,

a supply ship happened to arrive from the mainland at just the

right time, saw the crew's desperate situation and came to their

rescue.

By the

last day of work that first season, October 6th, the crew had

raised a temporary, cone-shaped platform called the "beacon

house" that they hoped would last through the winter.

|

Bell

Rock today. (Photo by Derek Robertson

licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share

Alike 2.0 Generic license).

|

When

Stephenson returned on May 25th, 1808, he found the beacon house

still standing. The first work he and his crew set out to do

was to excavate a round, two foot deep foundation pit in the

rock where the first course of granite stones that made the

base of the lighthouse would be laid. To get the stones from

the ship to the location, Stevenson also had the men lay a 300

foot long set of iron tracks. It took the enitre summer working

season, but by fall, three courses of stones had been laid and

the lighthouse rose four feet above the reef.

As construction

continued, Rennie spent less and less time on the project, finding

the difficult and dangerous conditions at the site not to his

liking. This was fine with Stephenson, who always thought he

had more experience with building lighthouses, anyway. He became

the de facto head architect, often working from his own designs

and ignoring Rennie's plans.

During

the third season the beacon house was expanded and some of the

men took to sleeping there rather than rowing back to the Sir

Joseph Banks for the night. They may have regretted this one

evening when a heavy storm rolled in and the men spent 30 hours

in a gale, clinging to the precarious looking construction.

Though the house took some damage, both it and the men survived.

Despite bad weather that summer, by the end of August the solid

bottom of the lighthouse was finished. It towered 31 feet above

the rock with the top seventeen exposed even at high tide.

In the

spring of 1810, Stephenson was determined to finish the lighthouse

by that winter. As the lighthouse climbed into the sky, however,

the work became even more difficult as high winds whipped around

the workers as they clung to a narrow scaffolding, working mortar

into joints in the exterior masonry. Even with this difficulty,

by the end of July the lighthouse had reached the height of

102 feet as the last stone was put in place.

|

Robert

Stephenson.

|

A heavy

storm in August caused damage and delayed the completion of

the interior for the lighthouse, but by the end of October most

of the lighthouse lamps, reflectors and 'fog bells' were in

place. The one thing that was missing were large sheets of red

glass that would be used to color the light so that it flashed

both white and red as an identification code, signaling to ships

that this was the Bell Rock beacon.

Operation

By February

1, 1811, the final pieces were put in place and the lighthouse

was put into service, forever ending the danger to sailors of

the reef underneath it. Four keepers maintained the light, three

at any one time out at the site, while the fourth one was on

leave on the mainland.

Though

the beacon was automated in 1998, the lighthouse still stands

today, the oldest offshore light still operating in the world.

It is a monument to Robert Stephenson who designed it, and the

brave men that built it. It endures as an engineering wonder

of its age.

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2015. All Rights Reserved.