Dinosaurs of the

|

A

early drawing of a Megalosaurus.

|

Science and dinosaurs became acquainted around

1815 through a gentleman named William Buckland. Buckland

had acquired some large fossil bones from Stonefield quarries

near Oxford, England. Buckland recognized these bones as belonging

to what appeared to be a lizard of enormous size. He named his

find Megalosaurus which means "Great Lizard." According

to his calculations, the animal must have exceeded forty feet

in length and weighed as much as a large elephant.

Though Buckland was not the first person to find

a Megalosaurus bone (Robert Plot described one as far

back as 1676) he was the first to realize that these fossils

belonged to an unknown class of huge reptiles.

In 1842 Richard Owen, of England, wrote

an article reviewing the fossil evidence of these large reptiles.

By then three species were well known: Megaloasurus, Iguanodon,

and Hylaeosaurus. Owen noted that all three animals had

similar structures in their vertebrae and decided that they

should all belong to a new sub-order of the Saurian order. He

coined the term of this sub-order Dinosauria, or "terrible

lizards" and the name stuck.

These huge lizards fired the imagination of 19th

century scientists and the general public alike. People marveled

at the drawings made from their early study of dinosaur fossils.

Scientists fought over excavation sites so they could be the

first to discover and name new species.

One early fan of dinosaurs was Queen Victoria's

husband, Prince Albert. He often attended Owen's lectures and

in 1852 was instrumental in convincing Owen to assist in creating

an outdoor exhibit of prehistoric creatures based on Owen's

ideas about how the creatures looked.

The Monsters of Sydenham Park

|

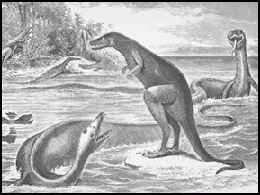

A

drawing of the Sydenham Park exhibit.

|

In 1854 Benjamin Hawkins, a sculptor, was

commissioned to make the full-size concrete replicas of the

dinosaurs and other extinct reptiles for Sydenham Park just

outside of London. The park was the new home of a huge glass

building known as the Crystal Palace which had housed the Great

Exhibition of 1851. The animals, designed by Owens and built

by Hawkins, were displayed in a natural setting. They included

Igauanodon, Hylaeosaurus, Megalosaurus, Plesiosaurus

and Ichthyosurus. The last two (being marine reptiles)

were shown swimming in a shallow lake.

The exhibit opened with much fanfare. On the first

night a dinner was held for twenty-one distinguished scientific

guests in the belly of one of the giant igauanodon statues.

Invitations to this gala event were sent out on artificial pterodactyl

wings. The scientists attending the dinner were so boisterous,

due to the large amount of alcohol they consumed, that their

singing could be heard across the entire park.

Owen's and Hawkins' interpretation of the creature's

appearances affected how dinosaurs and other large extinct reptiles

were drawn and viewed for a good twenty-five years. The truth

is that the men had very few bones to work with and their interpretations

were based as much on conjecture as physical evidence. Owens

instructed Hawkins to make the creatures look more like mammals

than reptiles because it fit his scientific theories. We now

know that dinosaurs looked quite different from the spectacular

models Hawkins produced. Still, the exhibit was a huge success.

Though the Crystal Palace burned to the ground in 1936, Hawkin's

models can still be seen today in Sydenham Park south of London.

|

The

dinner held in the Sydenham Park Igauanodon.

|

So far dinosaurs had only been found in Europe.

In 1858, however, the first American dinosaur was found in the

small town of Haddonfield, New Jersey. The creature was named

Hadrosaurus foulkii, after the town and the discoverer,

William Parker Foulke, and aroused interest in dinosaurs in

the United States. The Hadrosaurus was an extremely important

find. It was the first nearly complete dinosaur skeleton ever

seen and taught scientists that at least some dinosaurs walked

upright on two feet. Up to this point most scientists had thought

that all dinosaurs walked on four feet like other reptiles.

The Museum That Never Was

One-hundred miles north of Haddonfield in New

York City, success of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs in London

reached the ears of Andrew Green, head of the Board of Commissioners

of Central Park. At that time, in 1868, the park was under construction.

Green decided a Paleozoic Museum, like the one at Sydenham,

would be a nice addition. He wrote to Hawkins saying, "It gives

me great pleasure to propose to you to undertake the resuscitation

of a group of animals of the former periods of the American

continent."

New York City at that time had no significant

natural history museum or society and was jealous of cities

like Philadelphia which had the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Green felt that the paleozoic museum would bring a "degree of

culture and advancement" to the city.

Hawkins came to the United States and established

a workshop in Central Park to build the molds necessary to cast

the prehistoric creatures. The museum was to be quite spectacular.

An iron framework held up by columns was to cover a small park.

In the park, replicas of two Hadrosaurs were to be shown

under attack by the carnivorous LaeLaps. In a shallow

lake the marine reptile Elasmosaurus would frolic. Extinct

mammals, including mastodons, giant sloths, giant elk, and giant

armadillos would also be featured. The price tag for the project

was $300,000.

Learn

More about the Great Paleozoic Museum that was never

built by watching our flash

film.

|

The project was well underway in 1870 when the notorious politician

William "Boss" Tweed came to power in New York City. Finding

no way he could profit via illegal kickbacks from the museum,

Tweed determined to destroy it. He packed the park commission

with his own people who then voted to put a stop to the project

and destroy the foundations that had been laid.

|

The

dinosaurs Hawkins built still inhabit Sydenham Park. (Creative

Commons)

|

Hawkins persisted, however, and Tweed decided

more drastic action was needed. A year later thugs, sent by

Tweed, broke into the workshop and smashed the dinosaurs with

sledge hammers. Later, they came back and did the same to Hawkins'

molds and small scale models. Hawkins was shocked and disgusted

with this episode and after a stint on the staff at Princeton

University, returned to England. And so the Great Paleozoic

Museum of Central Park became the museum that never was.

The Great Bone War

The Elasmosaurus that was to be featured

in the Great Paleozoic Museum was a recent discovery of a scientist

named Edward Drinker Cope. Cope was associated with the

Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and spent much of

his time in Haddonfield, New Jersey, where the first American

dinosaur had been dug up in 1858. Cope had an arrangement with

the quarries in the area to sell him any fossil bones they found.

|

The

elasmosaurus with the head on the wrong end.

|

In the spring of 1868 Cope invited another distinguished

scientist, Othniel Charles Marsh from Yale University

and the Peabody Museum in Connecticut, to visit him. Cope showed

Marsh around the area quarries. To Cope's surprise, soon afterward

the stream of fossils he was getting from these quarries dried

up. Cope investigated and concluded that Marsh had paid off

the quarry owners to have new fossils sent to him. This incident

sparked a feud between the two men that would last almost thirty

years.

In 1870 the rivalry was raised to a new level.

Cope had just finished piecing together the skeleton of the

elasmosaurus. The elasmosaurus (whose name means "Plated

Reptile") was a long-necked, long-tailed marine reptile that

lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. Marsh examined Cope's

work and realized Cope had made the mistake of mounting the

head on the end of the tail. In an article he wrote Marsh jokingly

suggested that Cope should have named the creature Steptosaurus,

which means "twisted reptile." Cope was mortified and attempted

to buy up all the pictures of his mistaken reconstruction and

have them replaced with corrected versions. Cope didn't get

them all, though, and some drawings depicting the elasmosaurus

with its head on the short end, which is the wrong end, survive

.

The next year Cope returned the favor to Marsh

by stealing away one of his assistants and digging in one of

his excavations in Kansas. Neither Cope nor Marsh did much of

the actual shoveling, but employed collectors to do the excavations

for them. Since both Cope and Marsh were wealthy men and, as

one paleontologist once put it, neither was "overly scrupulous"

they could lure each others collectors away with promises of

more money.

This soon escalated into a full-scale competition

to see which scientist could discover the most new species and

amass the largest collection. Excavating a new find didn't mean

nearly as much as publishing a scientific report on the creature.

With this end in mind, Cope spent much of his fortune in buying

a controlling interest in the journal American Naturalist

so he could more easily speed his articles into publication.

Both Cope's and Marsh's articles became less and less informative

and more and more attacks on each other, thinly veiled as "scientific

criticism."

Out in the field, both men's collectors were busy

digging up fossils and spying on each other. In 1877 both teams

got wind of large bones at Como Bluff in Wyoming. This turned

out to be one of the most significant fossil beds ever found.

"...they tell me the bones extend for seven miles and are by

the ton..." wrote Samuel Williston, a collector, to Marsh.

The rival collectors started destroying minor

and incomplete fossils to prevent the other side from finding

them. Fights nearly broke out over digging sites.

Back on the east coast the feud, which had been

known only in scientific circles up till then, made the papers.

The front page of the January 12, 1890 edition of the New York

Herald led with the headline:

SCIENTISTS WAGE BITTER WARFARE

The article contained claims from Cope that Marsh

had stolen fossils, plagiarized articles and was generally incompetent.

The scientific community was embarrassed, but the Cope/Marsh

rivalry heightened the interested of the public in paleontology.

|

Othniel

Charles Marsh

|

|

Edward

Drinker Cope

|

The feud finally came to an end 1897 when Cope

(right) died after using up his entire fortune in the

dinosaur hunt. Marsh (left), who was better funded because

of his connection with the U.S. Geological Survey, was the final

winner having a larger collection than Cope and having discovered

more species.

However, there is a story that Cope offered a

final challenge to Marsh. After his death Cope bequeathed his

body to science. He directed that the volume of his skull was

to be measured. If Marsh did the same thing, then history would

know who was the smarter man.

Marsh didn't take up Cope's challenge, and today

we know such a measurement is not a very good indicator of intelligence.

Until very recently, however, Cope's skull sat on display in

a glass case at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia,

looking out over the collection he helped to amass. It remains

a reminder of those early years of dinosaur discovery in the

19th century.

Virtual

Cyclorama: The Paleozoic Museum That Never Was

Virtual

Cyclorama: The Paleozoic Museum That Never Was

|

Artists's

conception of the Paleozoic Museum of Central Park that

was never built (Copyright

Lee Krystek, 2002).

|

Copyright Lee Krystek

1999. All Rights Reserved.